The association between daily toothbrushing and hospital-acquired pneumonia

24-Jun-2024

3-minute read

By Barbara Quinn DNP, MSN, RN, ACNS-BC, FCNS

A systematic review and meta-analysis

Recently, fresh questions about the best oral hygiene protocols to prevent hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) have been raised. The release of the updated SHEA/IDSA/APIC Strategies to Prevent HAP in 20221 has reminded healthcare providers that oral hygiene is an essential intervention but has sparked new discussions about comprehensive oral care. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Ehrenzeller and Klompas (2023)2 looked at the role of toothbrushing.

Summary of the study

The study evaluated whether daily toothbrushing reduces the incidence of HAP, mortality, length of stay, and use of antibiotics. Fifteen studies met inclusion criteria: randomized control trials, hospitalized adults over age 16, oral care comparison that included toothbrushing versus no toothbrushing, and objective outcomes.

Fifteen trials were identified with a total of 10,742 patients. The risk of bias was assessed as low in seven (7) studies and high in eight (8). Only one (1) study was of non-ICU patients, so significant results were limited to ICU and patients on ventilators. Although the quality of evidence is moderate, the alignment between HAP and other objective outcomes increases certainty.

For ICU patients, the results demonstrated a significant association between toothbrushing and the reduction of HAP, ICU mortality, and length of time on ventilators and in the ICU. The frequency of toothbrushing was also examined. Toothbrushing twice daily was not inferior to three or four times. The study concludes that twice daily toothbrushing should be included in standard care for all hospitalized patients as an essential HAP prevention strategy.

Takeaway: Toothbrushing is essential

This study further validates that mechanical debridement of oral biofilm with a toothbrush is the gold standard of effective oral hygiene. Toothbrushing for every hospitalized patient should be woven into every hospital’s patient care process: policy, procedure, or protocol, staff education, quality improvement, and performance review.

The American Dental Association (ADA) agrees that an evidence-based toothbrush is irreplaceable. It should have soft bristles and be small enough to fit easily in the mouth. The bristles should be firmly attached to the brush head and not come off during use. The American Dental Association approval seal is preferred, to ensure the toothbrush's quality.3,4

Oral swabs are a convenient way to moisturize the mouth and lips, reducing the sense of thirst. However, they should not be used as a substitute for a toothbrush to remove plaque.5 Oral swabs are safe for one-time use only. Allowing the swab to “sit” in a cup of water should be avoided, as it may increase the risk of bacterial replication and infection. Extended exposure to water may also weaken the adherence of the swab to the stick, leading to detachment and posing a choking hazard.7

Toothbrushing without oral chlorhexidine is effective

This updated systematic review may reduce anxiety about the recent recommendation to withdraw chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) from routine care for ventilated patients. Although most studies included CHG as an adjunct to toothbrushing, the ones that brushed teeth without CHG had similar outcomes.

For those hospitals removing CHG from the VAP protocol, this update may provide an opportunity to refresh long-standing practice, prompting a review of the evidence, unit or hospital data, oral care supplies, and fresh patient and staff education. Policies, procedures, and order sets will need to be revised. As with any practice change, ongoing incidence monitoring is required to ensure VAP rates do not increase with the removal of CHG.

Toothbrushing twice daily is effective

Patients should receive a minimum standard of oral care twice a day, following the ADA recommendation for healthy individuals. Although some lower-level before and after studies have shown increased effectiveness with a higher frequency of toothbrushing, and the ADA Oral Care Protocol for Hospitalized Adults6 recommends four times a day, even twice a day is more than most patients are currently receiving, especially those not on a ventilator.

This updated evidence may help remove common barriers to determining the frequency of toothbrushing in the hospital. Compliance with oral care policies and procedures may increase for nursing staff who feel that brushing twice a day is feasible and “doable.” Nursing leaders may be willing to hold staff accountable to a more reasonable frequency. Patients, too, may be more likely to cooperate with a less frequent intervention, more like their home routine.

Reducing the risk of pneumonia is possible

Brushing patients’ teeth twice a day can help reduce the risk and incidence of HAP. Preventing HAP can result in multiple benefits. Patients benefit from surviving their hospitalization, remaining free of hospital-acquired sepsis, and being able to go home sooner. Family members benefit by being able to take their loved one home rather than managing a long-term rehab or nursing home transition. Nurses benefit from fewer rapid response calls, urgent phone calls to providers, new orders for tests, and new medication administration. The hospital benefits from a lower cost of caring for the patient and improved quality metrics.

Toothbrushing twice daily is an evidence-based intervention for hospitalized patients. It should be provided, promoted as essential, and prioritized by staff.

To learn more about our Oral Care products, click here.

Related products

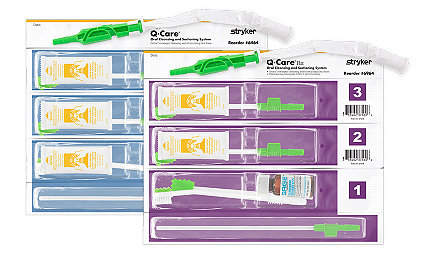

Sage oral hygiene systems for non-ventilated patients

Non-ventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia (NV-HAP) can occur on every hospital unit, including in younger, healthy patients. (1)

Learn moreSage oral hygiene systems for ventilated patients

The risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia is real. Reducing this threat takes a concentrated and coordinated effort. Our oral care kits for ventilated patients can help you perform appropriate oral care efficiently and effectively to aid in ventilator associated pneumonia prevention.

Learn moreSage oral hygiene tools

Our suction and non-suction tools allow you to deliver routine and essential oral care with confidence.

Learn moreSage Self Oral Care

Help address the risk factors associated with the #1 hospital-acquired infection, pneumonia.¹ The convenient, all-in-one system can remain at the bedside and doesn't require nurse assistance to use.

Learn moreBarbara Quinn, DNP, MSN, RN, ACNS-BC, FCNS is a paid consultant of Stryker. The data included in this presentation was collected by the author of this presentation. The opinions expressed are those of Barbara Quinn, DNP, MSN, RN, ACNS-BC, FCNS and are not necessarily those of Stryker. Individual results may vary.

References

1. Klompas M, Branson R, Cawcutt K, et al. 2022, Strategies to prevent VAP, ventilator-associated events, and NV-HAP in acute-care hospitals: 2022 update. ICHE, 43, 687-713.

2. Ehrenzeller S, Klompas M, (2023). Association between daily toothbrushing and hospital-acquired pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine. e1-e12.

3. Quinn B, Giuliano KK, Baker D, Non-ventilator health care-associated pneumonia (NV-HAP): Best practices for prevention of NV-HAP, American Journal of Infection Control, 2020, May;48(5S):A23-A27.

4. American Dental Association, ADA Seal of Acceptance, Available at: https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/ada-seal-of-acceptance Accessed June 4, 2024.

5. Pearson LS, Hutton JL. A controlled trial to compare the ability of foam swabs and toothbrushes to remove dental plaque. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39(5):480-89.

6. Mouth Care Swabs, UK, Knowledge Oral Health Care (kohc.co.uk). Available at: https://www.kohc.co.uk/mouth-sponges, Accessed April 2, 2024.

7. Davis J, Finley E, 2018, A second breadth: Hospital-acquired pneumonia in Pennsylvania, nonventilated versus ventilated patients. Pennsylvania Patient Safety Advisory, 15(3).

SAGE-OC-COMM-1104118_REV-0_en_us